A Business Guide for Sarawak’s Liberica Smallholders

By Dr Kenny Lee Wee Ting

22 August 2025

I. Reasonable Expectations About the Market

As Sarawak’s domestic coffee market has been heating up, we’ve received many inquiries in recent months from local coffee farmers and officers within the agriculture department—most of them about prices.

When many farmers first entered the trade a few years ago, a kilogram of coffee beans could only fetch RM12. Today, after mastering basic processing and grading, quite a number have successfully raised their prices to above RM30 per kilogram, and some have even sold at RM120 per kilogram—demonstrating the industry’s plasticity and room for progress.

Seeing this, a farmer recently asked me: can a kilogram of Liberica green coffee be sold for RM160? After examining the quality of his green beans, I felt that the information hidden in this question is both encouraging and cautionary.

To address these price-related questions, I’ve organized my thoughts here, in hopes of helping everyone better understand and plan the cost–profit mix for coffee. At this stage, farmers’ grasp of this topic is crucial to advancing our program.

First, the Sarawak Liberica Refinement Project rests on five core values:

Quality Improvement

Sustainability

Empowerment

Transparency

Market Access

Among these, we place particular emphasis on transparency and market access. All farmers participating in this program can clearly understand our published purchasing mechanism and the retail price ranges of our products in the market. The goal is to ensure fairness and trust across the entire value chain.

In addition to providing free training to help local farmers improve quality, we do not restrict whom farmers can sell to. As devout adherents of market economy principles, we do not believe any form of control or binding is particularly meaningful.

When we encounter truly committed farmers and high-quality coffees, we are willing to pay higher prices to compete with other buyers. This not only acknowledges quality but is also the best way to avoid predatory underpricing and to meaningfully reward farmers for their labor.

Because only when farmers are winners in this game can Sarawak’s coffee sector truly move toward sustainable development.

That said, the path to success for farmers involves many challenges. Beyond learning professional cultivation and processing methods, understanding the coffee market is equally important—after all, this is a business. Setting aside the Liberica crop-economics we’ve discussed previously, today we’ll look at value from the market end.

II. The Complexity of the Coffee Market

Coffee is one of the world’s most-traded commodities—not only in volume but also in the complexity of market segmentation. This complexity arises from the interaction of different coffee types (e.g., Arabica, Canephora/Robusta, Liberica) with diverse consumption cultures around the world. Add to this the rise of the “specialty coffee” market over the past 20 years, and price differences for green coffee can sometimes be bewildering.

We can look at the current 2025 international green-coffee landscape. A commercially acceptable coffee, purchased domestically from a green-coffee merchant, might be around RM26/kg, while a Best of Panama (BOP) auction champion can reach RM127,567/kg (US$30,204/kg). The gap between them is more than 3,600-fold. No wonder many local farmers feel lost—worried about being misled and unsure how to calibrate their pricing strategy.

As someone with over a decade of hands-on experience in international coffee trade and a certified taster with several international coffee bodies, I’d like to offer some reliable guidelines for your reference.

As noted in our earlier articles, Sarawak’s Liberica sector is largely a smallholder economy: most farmers cultivate 300–600 trees, similar to the Ethiopian pattern and unlike the large-estate model in some countries. That means there is no economy of scale. Coupled with Sarawak’s relatively higher labor costs than neighboring countries, the only path for farmers to benefit is to turn Liberica into specialty coffee.

Be aware that in Malaysia, local kopi-O roasted coffee often retails at RM30–RM40/kg. At that level, the most that roasters can pay farmers for green beans is around RM15/kg. This price tier simply cannot support a viable Liberica-growing industry.

So what is specialty coffee? Traditionally, coffees that score 80+ are called “specialty.” Of course, this standard is under challenge in new market environments—and it’s not directly applicable to Liberica. Yet since Liberica lacks its own scoring system for now, we can still borrow this benchmark as a rough reference.

If we refer to the SCA and NZSCA data, the rough median price for coffees scoring 80–85 is about US$6.03/kg (≈ RM25.40/kg)—that is, the price at which local farmers might sell to middlemen.

Once middlemen export the coffee—after adding freight, handling, and taxes—the cost can land around US$8.00/kg (≈ RM34.00/kg). Note: these prices assume graded coffee with no defects, no taints, moisture 10–12%, and clean current-crop beans.

III. What Is a Fair Price for Sarawak Liberica Green Coffee?

Because Liberica has yet to develop a mature sensory scoring system like Arabica, it’s difficult—at least for now—to build markets like those so-called “90+” lots sell for hundreds of dollars per kilogram. We can only rely on experience to decide when a given quality has reached “specialty.”

If we want Sarawak Liberica to enter the global specialty green market and compete with other species, then for a lot that’s graded, defect-free, clean, and from the current crop, a reasonable farm-gate price can reference the Arabica specialty median—around RM26/kg. Given Liberica’s rarity and processing characteristics (often with lower conversion yields), I believe RM32/kg and above is a more flexible and realistic expectation.

This reference is based on the 2025 market analysis. If farmers can consistently maintain quality at this level and price around RM32/kg, there will be competitiveness and feasibility for accessing international markets.

The scenario above refers to selling to green-coffee intermediaries. If farmers can directly connect with specialty roasters—especially overseas buyers—prices may rise further.

In our actual procurement experience, we typically purchase from general farmers at around RM35/kg. For those who have worked with us long-term, maintain consistent quality, and keep improving, we pay RM48–RM65/kg, or even higher. But to reach such values, consistency matters as much as quality. In Sarawak’s hot and humid climate, maintaining stable quality is by no means cheap.

If we procure at RM48/kg and add freight plus our team’s labor and time for professional roasting and cupping/grade evaluation for each batch, plus the communication required with individual smallholders, our per-kilogram green-bean cost easily rises to around RM65/kg.

Sometimes, when 20 independent farmers in one village bring in their beans, doing QC and grading, roasting, cupping, record-keeping, and communication one by one can take our team two full days.

Although the quality of Sarawak Liberica has improved significantly in recent years—no longer showing the musty, rotten-wood notes and obvious defects common in the past—there remains a sizeable gap before we can command several hundred ringgit per kilogram. From harvesting, fermentation, drying, and storage to transport, there is still plenty of room to improve.

Also remember: not every farmer in Sarawak can achieve RM48/kg quality. For now, based on our calculations, as long as a farmer keeps costs in check and meets basic quality standards, RM32/kg is a conservative, safe, and steady sales target.

Anchor to this price point and, on the upside, you may find buyers who will pay more; on the downside, there is no shortage of outlets—we can absorb tens of tons per year without issue.

Of course, if some farmers find buyers willing to pay higher prices, that’s excellent. Among our partner farmers, some have successfully sold green beans at RM120/kg. In other words, through working with us, they’ve managed to upgrade from RM12/kg quality to RM120/kg—a very encouraging result.

Nevertheless, everyone should understand that Liberica remains a niche coffee. Such high premiums often embed added value beyond bean quality itself: cultural meanings, community stories, and scarcity. While these one-off niche deals are inspiring, they are often non-repeatable or short-lived, and as Liberica supply grows, prices can quickly revert to the mean. Farmers should avoid being misled by momentary price spikes when planning.

From a green-traders perspective, if we buy at RM32/kg and add freight, storage, labor, QC, packaging, and market development, the final cost per kilogram can reach RM50. Given Sarawak’s very small overall output, economies of scale are absent. This means that selling below RM70/kg often amounts to selling at a loss for the green-traders.

However, RM70/kg is far above the international specialty median, so there will be pressure in sales and market acceptance.

Therefore, for farmers, when planning cultivation and sales, using RM32/kg as a base case to think through costs and margins is a more prudent and realistic choice.

For the Sarawak Liberica Refinement Project, our challenge is to support over 500 farmers across Sarawak and help them establish a sustainable production model—with more farmers joining continuously. Apart from our two Earthlings Coffee owned experimental farms, we are not focused on elevating a specific area to chase “competition coffees” and extreme prices. Instead, we aim to develop Liberica into a coffee for everyone.

We are currently working with the ARC of the Department of Agriculture Sarawak to develop more advanced fermentation methods to improve quality. We believe that in the future Sarawak coffee will see both overall quality and price increase—prospects worth anticipating.

IV. Isn’t Roasting and Selling Your Own Coffee More Profitable?

In today’s age of information transparency, market pricing has become clearer. Many farmers see retail prices for roasted coffee on city shelves running into the hundreds per bag and naturally infer that roasting and selling themselves might earn far more.

While this idea seems reasonable on the surface, implementation is far more complex. Successfully selling your own roasted coffee requires not only significant investment in equipment but also time and resources to learn professional roasting skills—including precise control of roast curves—to unlock flavor and truly enter the high-price market.

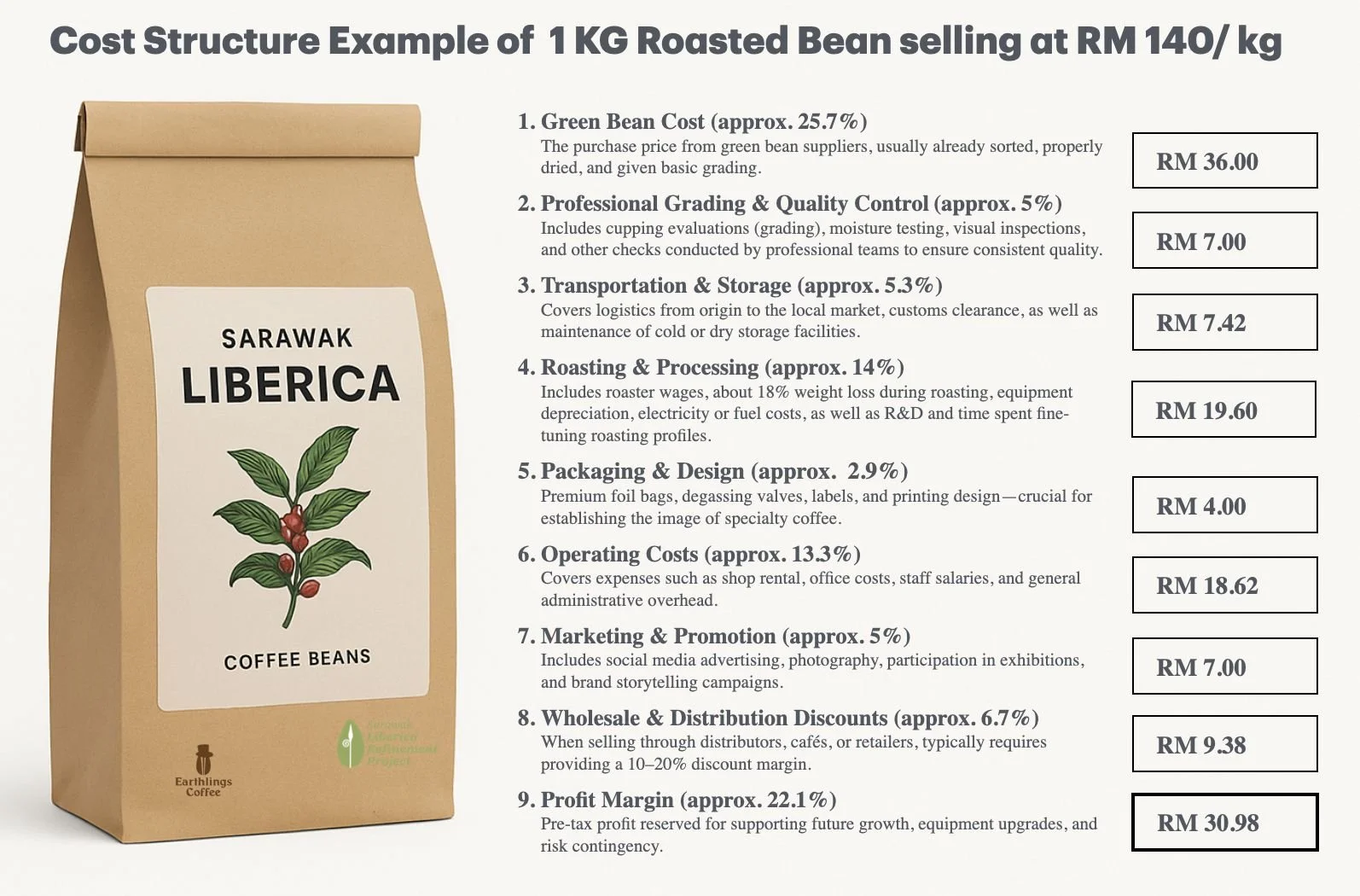

To make the actual cost of roasted coffee clearer, here’s a concrete case to help weigh inputs and risks.

Suppose you see a 1 kg bag of roasted coffee on a city shelf priced at RM140. What should the green coffee cost for that bag be? Here is one possible breakdown:

1. Green Coffee Cost (about RM36 / 25.7%) Purchased from a green-merchant, typically pre-screened, stably dried, and basically graded.

2. Professional Grading & Quality Control (about RM7.00 / 5%) Includes cupping/grade evaluation, moisture testing, visual inspection—ensuring stable quality.

3. Transport & Storage (about RM7.42 / 5.3%) Logistics from origin to local warehouse, customs clearance, and cold/dry storage upkeep.

4. Roasting Process (about RM19.60 / 14%) Roaster wages; ~18% weight loss during roasting; equipment depreciation; utilities; plus R&D and time spent refining roast curves.

5. Packaging & Design (about RM4 / 2.9%) Quality foil bags, valves, labels, and design/printing—critical to specialty brand image.

6. Operating Expenses (about RM18.62 / 13.3%) Shop rent, office overhead, staff salaries, management, and other routine costs.

7. Marketing & Promotion (about RM7 / 5%) Social media ads, photography, exhibitions, and brand-story development.

8. Wholesale/Channel Discounts (about RM9.38 / 6.7%) If sold via distributors, cafés, or retailers, a 10–20% margin is typically needed.

9. Profit (about RM30.98 / 22.1%) Pre-tax profit reserved for growth, equipment upgrades, and risk buffer.

In other words, the go-to-market costs can far exceed the green coffee itself. For a 1 kg bag priced at RM140, after deducting all these items, the remaining profit is RM30.98. After a 24% business tax, the actual profit is even smaller.

This is why many businesses re-pack into 250 g or 150 g formats to increase perceived value—though packaging and labor costs also multiply.

In short, farmers who roast and market their own coffee must also bear go-to-market costs. Without brand strength, competing is hard. Relying solely on “scarcity” and “local sentiment” is unsustainable as a strategy.

In fact, in Sarawak’s market conditions, consistently selling a 1 kg bag at RM140 is difficult; RM110/kg may have a chance. Note that many Arabica roasts on the market sell for RM80/kg.

A bigger challenge for Sarawak’s farmers is that many live in remote inland areas far from cities. Well-processed green coffee can be stored for one to two years, while roasted coffee stays at its best for only a few months before quality declines rapidly due to oxidation.

V. Conclusions & Recommendations

In sum, from a long-term perspective, Sarawak’s farmers should focus on improving green-bean quality. Only stable, high-quality green coffee can enter larger international markets and become a globally recognized “hard currency.” Specialty-grade green coffee has higher storability, shippability, and trading flexibility, crossing geographic and seasonal limits—making it the most sustainable product form.

If conditions permit, self-roasting and direct marketing can be pursued as adjacent lines of business. But they must be built on solid quality and stable supply, with a clear understanding of the technical, competitive, and time-sensitivity risks in roasted-coffee sales.

Therefore, we recommend a dual-track strategy:

1. Use high-quality green-bean trade as the primary economic pillar.

2. Develop local roasted-coffee brands as a secondary business, gradually building brand recognition and extending the value chain.

In the coming years, Sarawak coffee’s key breakthroughs will come from a deeper exploration of Liberica’s flavour diversity, varietal selection and cultivation, post-harvest and fermentation innovations, combined with global market education and cultural communication—to build Sarawak’s reputation as a leading origin for high-quality Liberica.

It’s also worth noting that, to my knowledge, thousands of acres of newly planted Liberica in Sarawak will gradually come into production over the next few years. This is exciting, but it also means surging output, fiercer competition, uneven quality, and price pressures.

How to avoid falling into a red-ocean price war amid these shifts—while preserving farmer margins and improving overall quality—will be our next collective challenge. In the next article, I will delve deeper into this topic and propose concrete strategies.