What is Specialty Coffee Now with Coffee Value Assessment?

by Rave S Kwok

The traditional 80+ system

For decades, we have learned that specialty coffees must have a cupping score of 80 and above.

However, people outside the coffee industry often don’t understand how this score comes about. This makes it difficult for us to convey what specialty coffee is to them.

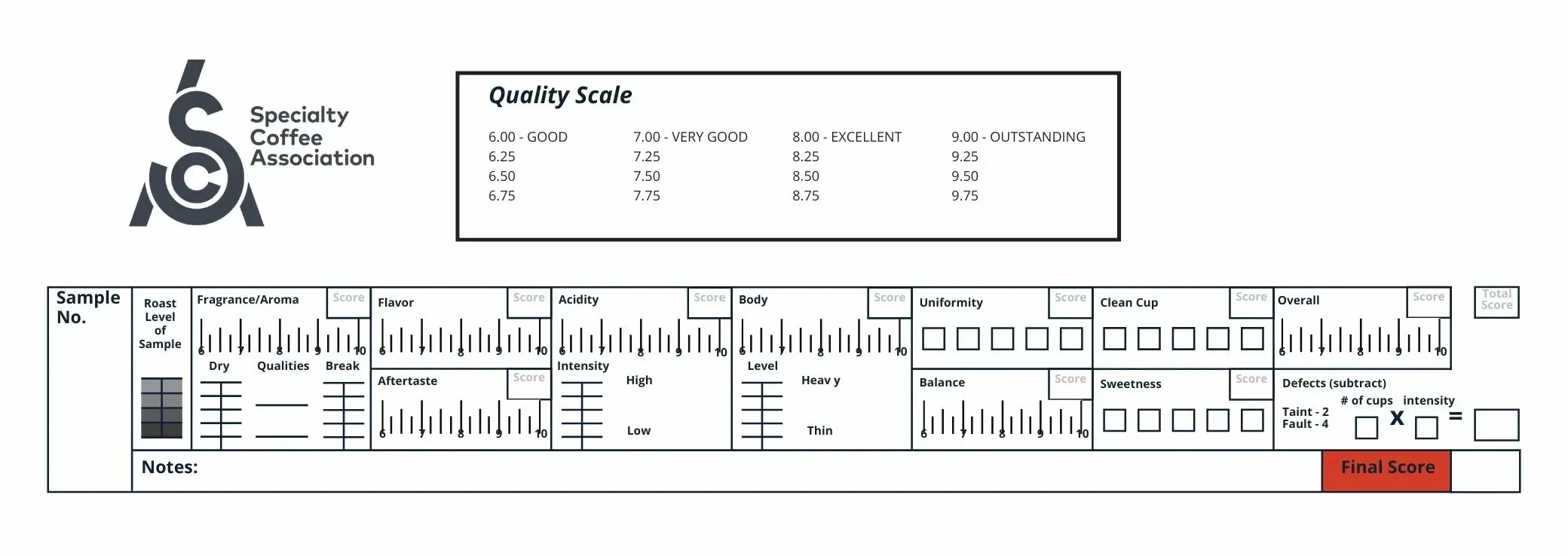

There are more than 8,000 active Q Graders worldwide. They are trained and certified by the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI) to assign a final score to each coffee they cup (evaluate). This score is calculated based on the perceived quality of a set of sensory attributes marked in a technical form created by the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA) in 2004.

Source: SCA

The objective of Q Graders is to establish a common language between other calibrated graders, and that language is based on scores. Scores also help to bridge communication between coffee buyers and producers to decide on a coffee’s economic value, and motivate farmers to improve green quality.

However, scores alone cannot define specialty coffee for the general consumer.

Or can they?

Coffee is more than just numbers

Coffee scoring systems such as Q and Cup of Excellence (COE) are useful in quality grading and price-tagging and finding a winner in competitions, but their limitations show when serving different purposes in the world of consumers from different market segments.

We’ve conducted many public cupping sessions over the years. I noticed many customers can’t really tell apart higher-scoring coffees (90+) and average-scoring coffees unless we “train” them to appreciate those specific nuances. Some insist that specialty coffee is only special to its drinker. After all, we drink coffee, not numbers. Our preference has the final say on how much we are willing to pay for a cup, and that is a subjective experience difficult to standardise across individuals.

Earlier this year, Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) took over the Q Grader Program from CQI and swiftly replaced its old scoring system with the new Coffee Value Assessment (CVA). Let’s skip the drama behind the whole takeover and focus on what this new system is about.

Coffee Value Assessment (CVA) in a nutshell

Coffee has more than one type of value (economic); CVA takes into consideration the aesthetic value and human value in its design. SCA believes adding these two values helps paint a clearer picture of specialty coffee, but these values can be vague and hard to measure. For this, the new system offers four forms to evaluate a coffee from different scopes:

Physical Form (same as CQI’s Green Coffee Assessment)

Extrinsic Form (all the info about a coffee on paper)

Descriptive Form (describe a coffee without value judgement)

Affective Form (record how much you like or dislike a coffee and why)

Each form serves a different objective and measures/records a coffee’s attributes. I won’t go into details as I go through each one from my own understanding; you may find the forms here. SCA also made it clear that the four forms should not be used side-by-side to avoid biases during cupping.

I. Physical Form

Physical assessment remains the most objective way to evaluate coffee quality: more visible defects indicate lower quality and less economic value (price). Not much has changed here; face value still matters in the coffee market.

II. Extrinsic Form

What else adds to the face value of a product? Story-telling and extra information. The Extrinsic Form—still in its beta phase—is where you can find everything about a coffee even before the coffee arrives at your door. Such as farm info, processing methods, bean size, awards won, etc. If coffees had birth certificates, this form is where you attach them.

III. Descriptive Form

Sensory attributes are now measured with two mindsets.

Imagine sipping coffee in a therapy chair with Jung, jotting down anything that comes to mind without judgment. The Descriptive Form is to find as many descriptions and sensory connections to a coffee, without thinking about good or bad. It’s like identifying what musical instruments are playing in a piece of music; it doesn’t matter if you hate the music. How loud is each instrument? This is equivalent to describing the intensity of the smell, taste, and haptic attributes of the coffee using a 15-point scale. Just remember, if you rate a coffee low in sweetness and high in acidity, it still doesn’t mean the coffee is bad (it’s just a loud violin playing).

IV. The Affective Form

Affective assessment is where you roll up your sleeves to give your opinions about a coffee. Each of the eight sensory attributes—from dry fragrance to the overall impression of a coffee—is rated on a 9-point hedonic scale. For example, you could rate the aroma of this coffee a 9 (it smells like everything you love) or a 1 (you need to cover your nose). Justify your rating in the notes. You can’t just write down “Floral” and assume it’s a positive remark. It has to be something along the lines of “I like the hint of floral aroma in this coffee,” to make it worth a 7. Defects are also to be identified in this form and deducted from the final score. This is the only part of CVA where scoring is still relevant, but it’s truly subjective.

The old vs. the new

The old scoring system aims to have every grader land close to the average score for each coffee sample. They call this calibration, where all Q-graders at the cupping table try to put their individual preferences aside and benchmark their scores to the norm of the group. Coffees with flavour notes such as blueberry or jasmine will easily score 8.5 or above in the Flavour category, while herbal, wood, and grain will usually sit below 7. Good acidity will also carry a coffee further into higher specialty, along with other attributes that I won’t dive into here. The final score is often an “objective” verdict on whether a coffee is specialty, because it’s not just from one average joe (who might dislike acidic coffee) but a group of trained “pros”.

Score calibration is no longer relevant with CVA; individuals from different cultures won’t need to conform to the mainstream flavour preference. If you like Thai cuisine more than French, you’d give the herbal spicy dish a higher (affective) score despite what the Europeans at the same table think. But everyone should be able to accurately identify the distinctive notes in the cuisines. If you painted a Van Gogh in your Descriptive Form, while others painted Rembrandt, either you or they need to polish their sensory skills. But which painting is more specialty depends on which one has more harmonious colours and detailed paint strokes (the coffee with more distinctive sensory attributes and extrinsic info).

Can CVA Redefine Specialty Coffee?

Specialty coffee is still a difficult phrase to define by just one system. It’s a dynamic concept that evolves with time. You may or may not agree with defining specialty with numbers, but 80+ = specialty was a clear and concise definition that many coffee professionals had used for decades to decide how much they should pay for a coffee and who to sell it to. In comparison, CVA is a bold step forward in embracing cultural and market diversity. It may be less efficient now when it comes to defining what specialty coffee is, but it’s more versatile and usable in more contexts in the vast coffee market.

Despite the controversy, I think CVA is the more holistic approach to coffee evaluation compared to the old scoring system, although they are not the first to come up with such an approach. Almost a decade ago, Coffee Consulate (Germany) created a cupping form to profile coffees without assigning a judgmental score, but this is for another time and place.

Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.