Malaysia’s Hidden Treasure: The Past and Future of Liberica in Sarawak

By Dr Kenny Lee Wee Ting

From the Afterglow of the Age of Exploration to the Hills of Matang

Charles Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak

At least for someone like me—someone captivated by the sweeping tales of the 15th-century Age of Exploration—coffee is, in its essence, a kind of spice. That romantic era, when people gathered at bustling trade ports, eyes fixed on the horizon waiting for ships to return with exotic aromas and treasures from the East, has long passed.

And yet, if there is still a substance today that can lock in the richness and diversity of terroir on the tongue, it must be coffee. Though, admittedly, not many would think of coffee as a spice.

In the mid-19th century—the twilight years of the maritime empires—Sarawak was under the rule of the Brooke dynasty. Between 1865 and 1870, Italian naturalist Odoardo Beccari conducted multiple expeditions in and around Kuching and Matang. His renowned book Wanderings in the Great Forests of Borneo (1904) documented extensive botanical observations and field routes, which in turn brought Matang’s natural history into global scientific awareness.

It was during this period that Charles Brooke, the second White Rajah of Sarawak, established an experimental plantation in Matang to trial coffee and tea cultivation. While early Arabica trials at low elevation were unsuccessful, these early efforts paved the way for the eventual introduction of Liberica, positioning Matang as a symbolic landscape for Sarawak’s “first wave of coffee experimentation.”

The Matang of that era also bore witness to the presence of British botanical artist Marianne North. In 1876, she painted scenes such as Strange Plants in the Forests of Matang, Sarawak, works that are now housed in the Marianne North Gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. These paintings offer a rare visual slice of the era’s natural exploration and agricultural trials.

Fast forward more than a century to 2023—during a visit to Dr. Aaron Davis, renowned coffee botanist at Kew Gardens in London—we had the rare opportunity to view many of Marianne North’s original paintings of Sarawak. It was a surreal moment, as if history and the present moment were in dialogue across time. Unfortunately, photography inside the gallery was not permitted.

View of Matang and River, Sarawak, Borneo by Marianne North

A Century-Long Bond: Sarawak and Liberica Coffee

According to the archival timeline of the Department of Agriculture Sarawak (DoA Sarawak), Charles Brooke officially introduced several crops in 1875—including Coffea liberica (Liberica), cocoa, and oil palm. Although these crops did not achieve immediate commercial success, this marked a crucial turning point when coffee cultivation in Sarawak shifted from exploratory trials to systematic crop introduction.

Historically, Sarawak may well have been the first state in Malaysia to introduce Liberica. In Peninsular Malaysia (West Malaysia), the earliest confirmed Liberica plantation was established in 1879 in Linsum, along the Perak River in Negeri Sembilan, by T. Heslop Hill.

On page 369 of Wanderings in the Great Forests of Borneo, Odoardo Beccari clearly states that while Arabica coffee trees planted in lowland Matang did grow, they failed to bear fruit. He also noted that at the time, no fewer than 650 acres of Liberian coffee were being cultivated in Sarawak.

From that point onward, this species of coffee continued to be propagated and cultivated by local smallholders. Over time, among Sarawak’s Indigenous communities, Liberica acquired a localised name: Kupi Dayak, or “Dayak coffee.”

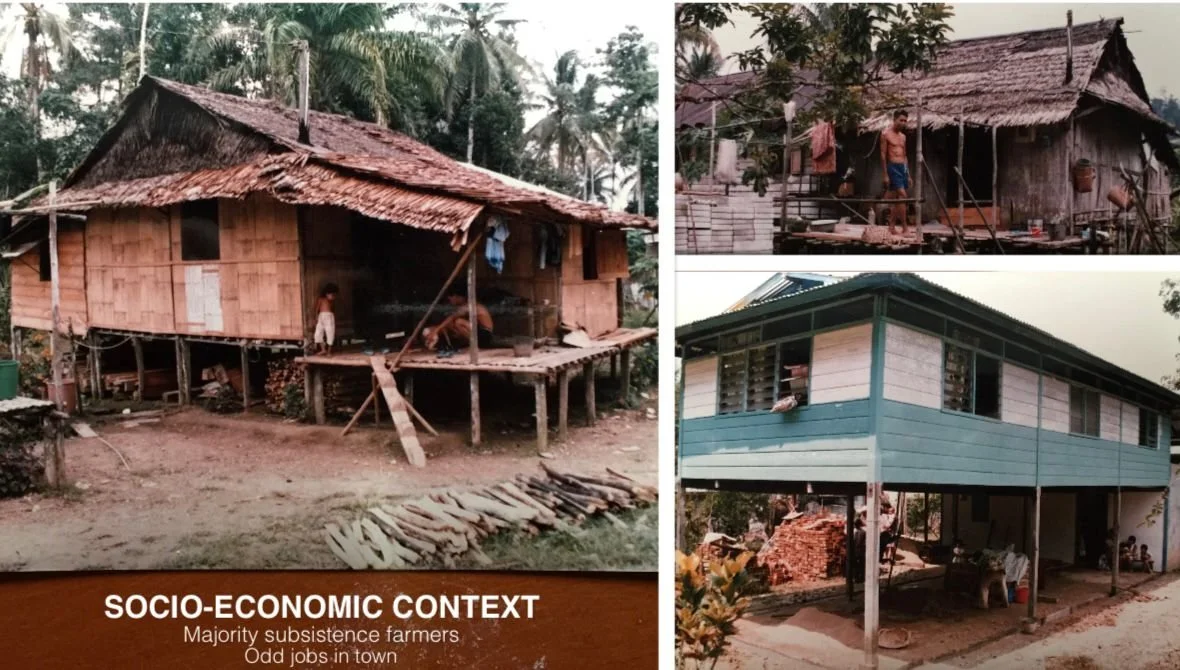

In 1993, community leader Datu Ose Murang initiated a large-scale coffee planting program in Kampung Ngiromis, near Bau in greater Kuching. Spanning around 120 hectares, the project mobilised more than 56 Bidayuh families. The main varieties planted were MARDI’s Liberica MKL-2-4 and Robusta MKR-2-5.

At the time, this initiative carried high hopes of revitalising the rural economy and community livelihoods. However, limited post-harvest processing technology and prolonged global price stagnation ultimately hampered its sustainability.

Years later, at the 2019 Borneo Coffee Symposium, Datu Ose Murang personally revisited and shared this valuable chapter of history. His account has since become a vital piece of Sarawak’s coffee narrative. According to his recollection, the planting phase was highly successful. Unfortunately, unforeseen changes in management later disrupted the program’s continuity—a regrettable outcome.

The Ngiromis project, led by Datuk Ose Murang.

Coffee project carried out by the Bidayuh ethnic group. Photo credit: Datuk Ose Murang

Zooming Out: The Broader Coffee Landscape of Malaya–Malaysia

Shifting our lens away from Borneo, we turn to the Malay Peninsula at the close of the 19th century. Between the 1870s and 1890s, the expansion of tin mining, road and rail infrastructure, and colonial capital gave rise to a brief coffee boom. During this time, sizeable plantations were established in Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Perak, and Johor. Among the planters were individuals returning from Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), who brought with them experience, knowledge, and investment capital.

Historical texts like Bygone Selangor document the rise and fall of coffee estates in places such as Batu Caves and Ginting Bedai. These records also reveal early experiments with Liberian coffee (now recognised as Liberica) by pioneers such as T. Heslop Hill.

However, the boom was short-lived. In 1869, coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) broke out in Ceylon and swept through the tropical coffee belt over the next decade, drastically reshaping global coffee supply chains. Compounding this devastation, the global coffee market experienced severe price declines toward the end of the 19th century, driven in part by massive coffee expansion in Brazil. In Malaya, this double blow accelerated the shift away from coffee—by the 1890s, many estates pivoted to rubber, a crop with higher returns and lower risk.

Historian Stuart McCook has described coffee leaf rust as “an ecological turning point in global coffee history,” and this lens helps us better understand the strategic crop shifts of the era.

In response to these dual crises—one microbial, one economic—colonial powers began seeking more disease-resistant coffee species in Africa. It's worth noting that the modern-day trio of commercially dominant species (Arabica, Robusta, Liberica) did not exist back then. Coffea canephora, better known as Robusta, was only discovered by Belgian explorers in 1870, a year after the leaf rust outbreak. It wasn’t formally named by French botanist Louis Pierre until 1895, and only began widespread cultivation in the early 20th century.

Had you traveled back in time to the 1870s, you would’ve found a coffee world dominated not by Arabica and Robusta—but by Arabica and Liberica. Although Liberica’s cultivated footprint was comparatively small, it was still regarded as one of the two major species alongside Arabica.

A hundred-year-old Liberica estate in Sungai Pelek, Peninsular Malaysia.

Eventually, as countries within the tropical “coffee belt” adapted to new realities, Robusta emerged as the preferred species for its disease resistance and high yield. Malaysia, lacking high-altitude terrain suitable for Arabica, was gradually left behind. Along with Liberica, the country faded from the global coffee conversation. For the next three decades, Malaysia was largely excluded from the specialty coffee movement.

But global warming is beginning to change this narrative. What was once seen as a curse—Malaysia’s lowland tropical climate—is now being reassessed as a potential advantage in a warming world.

Some forward-looking institutions began sounding the alarm decades ago. Germany’s Coffee Consulate, Malaysia’s My Liberica, House of Kendal plantation, and the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) all began promoting so-called “niche species” like Liberica as early as the 2000s, emphasising their untapped potential. Today, those early calls are finally gaining global attention.

Why Liberica? The Strategic Species Choice of Malaysian Coffee

Today, any discussion about Malaysian coffee inevitably centres around Liberica. According to an industry overview by the Food and Fertiliser Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region (FFTC), roughly 90% of Malaysia’s commercially cultivated coffee is Liberica, while Robusta (Canephora)accounts for about 10%. Arabica, by contrast, is found only in small-scale, highland farms—such as in Lawas and Bario in Sarawak, and in the Cameron Highlands of Pahang.

This makes Malaysia a true outlier on the global coffee map—the only coffee-producing country among more than 80 worldwide that primarily grows Liberica.

Even in Liberica’s birthplace, Liberia, the dominant crop is now Robusta, and Liberica is rarely mentioned. Other countries—such as the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Fiji, Uganda, Cameroon, and Sierra Leone—do grow small quantities of Liberica, but its commercial share in these countries remains minimal. According to information provided to me by Mr. Jason Liew, owner of My Liberica coffee estate, there is currently a Liberica cultivation project in Fiji covering several thousand acres.

In Latin America—from Brazil and Costa Rica to El Salvador, Panama, and Guatemala—Liberica is viewed more as an experimental or conservation species rather than a commercially viable crop.

Why Did Liberica Thrive in Malaysia?

Liberica is more tolerant of environmental stresses than Arabica and Robusta, and it can be grown at low elevations in warm tropical conditions.

That Malaysia has become a rare sanctuary for Liberica can be attributed to a mix of geographical, climatic, and economic factors:

The country’s lowland topography, high humidity, hot temperatures, and soil types make it poorly suited for Arabica.

Labor costs and infrastructure limitations also shaped what was practically viable.

Liberica’s natural resilience—its ability to fruit at low to mid elevations, and its strong resistance to pests and diseases—made it a pragmatic choice for local farmers.

Despite accounting for less than 1% of global coffee production, Liberica is not a low-grade substitute. On the contrary, recent research and market trials have revealed its unique flavour profiles and high genetic and sensory diversity. When properly processed, Liberica has the potential to enter the specialty coffee market as a distinctive and premium product.

A Global Rethink of Flavour Aesthetics

The growing interest in Liberica coincides with a larger rethinking of sensory paradigms within the global specialty coffee community. As mentioned in the previous article, as of 2025, 133 coffee species have been formally identified. The difference between species can be as vast as the difference between strawberries and mangoes. It makes little sense to evaluate all of them using the same flavour framework developed solely around Arabica.

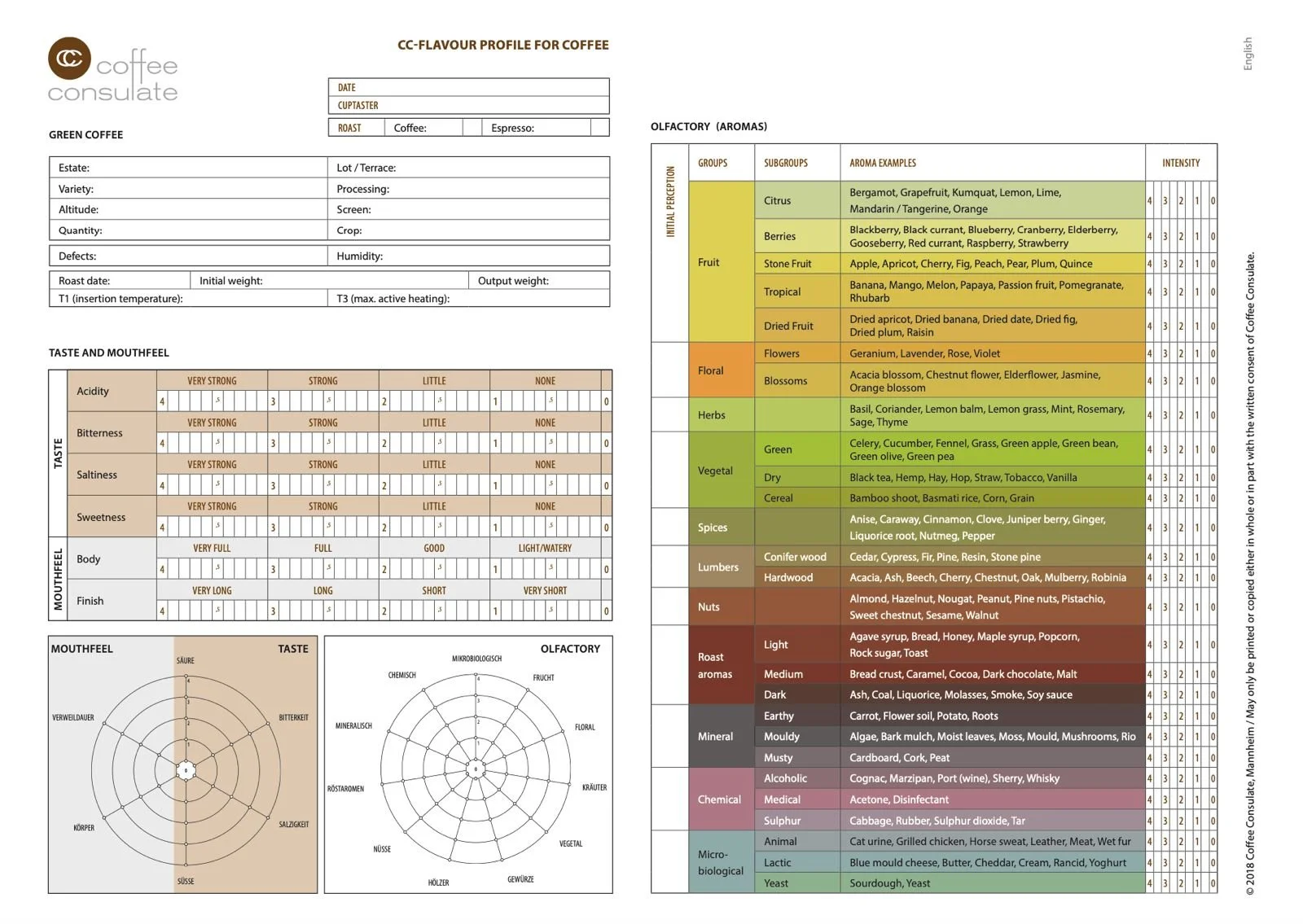

Original Coffee Consulate cupping sheet.

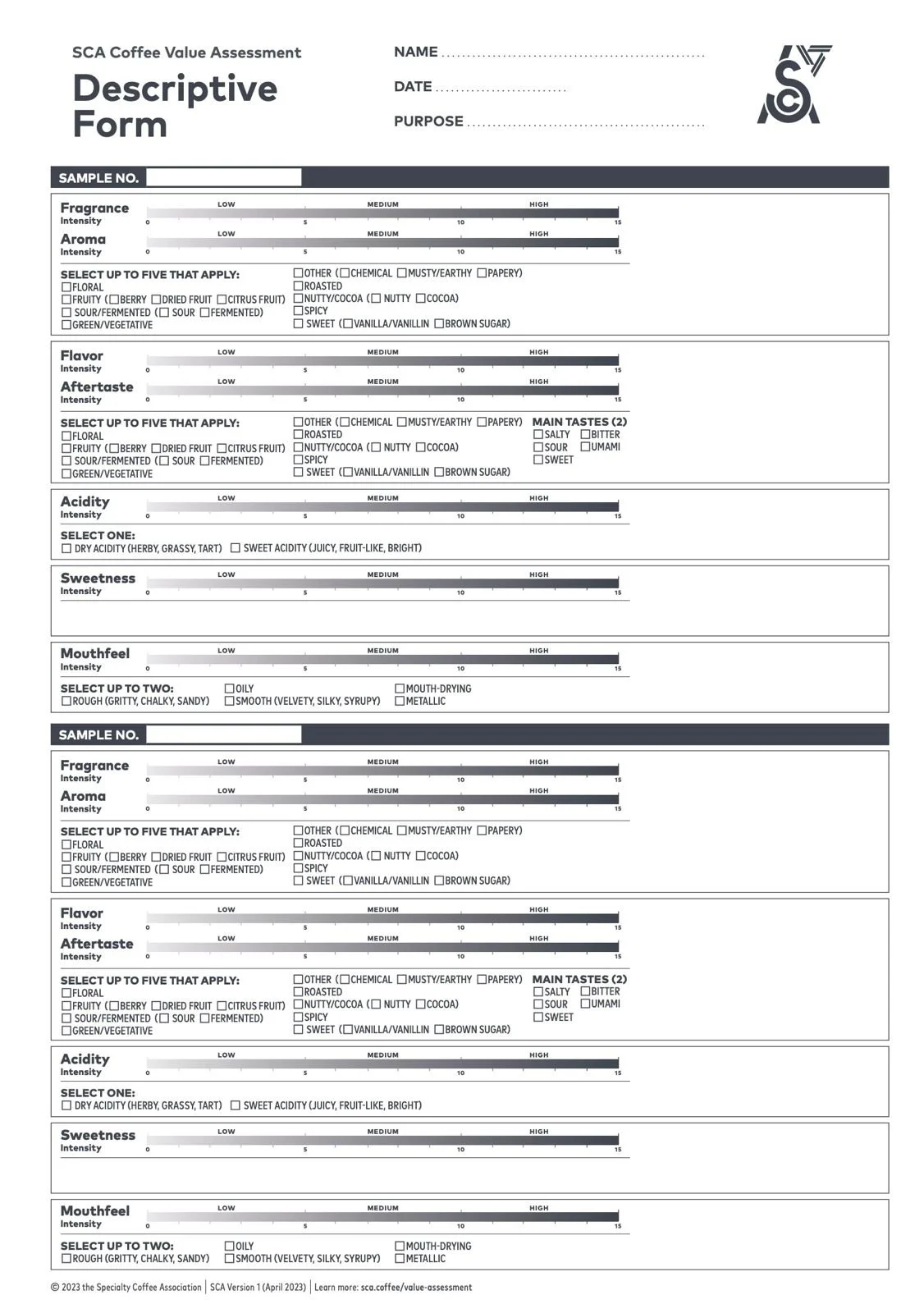

The new SCA Coffee Value Assessment (CVA) Descriptive Form.

The Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) has recognised this and is actively pushing for reform. Its newly introduced CVA cupping protocol emphasises objective, descriptive tasting rather than assigning simplified numerical scores. The system respects the subjective preferences of diverse markets and cultures, instead of enforcing a one-size-fits-all hierarchy of taste.

Key figures like Mirna Nagi, Peter Giuliano, and Mario Fernandez have recently reached out to our team to explore the inclusion of localised flavour vocabularies in SCA’s upcoming flavor wheel revisions. These efforts aim to break old conventions and unlock new possibilities for lesser-known species like Liberica and Excelsa.

Kopi Dayak and the Local Economy: The Pulse of Sarawak's Indigenous Coffee Culture

Back in Sarawak, the cultivation of Liberica by interior indigenous communities has persisted across both colonial and post-colonial eras, sustained under the local name Kopi Dayak. For much of the recent past, these Liberica trees—scattered across rainforest villages—were not grown for commercial purposes but instead served as household crops, tucked in the corners of backyard gardens and harvested for personal consumption.

Due to Sarawak’s hot and humid rainforest climate, combined with a lack of post-harvest knowledge, most traditional processing methods were unable to control fermentation or drying effectively. Defect sorting was virtually non-existent. As a result, such coffee often carried dominant notes of mustiness and wet wood, far removed from what is considered specialty-grade by global standards.

Most of this coffee was sold at very low prices to local traditional roasters and processed into deep-roasted Kopi-O (Sometime Carbonised—a common black coffee beverage in Malaysia.

I once heard an elder matriarch in Long Watt, a Kayan-majority village deep in Sarawak’s interior, recount her memories:

“As a child, I would help my parents pick coffee cherries in our backyard. After a few days of sun-drying, we would crack the parchment manually using wooden pestles. I’d carry a small plastic bag of beans with them down the winding Baram River, hours by boat to Marudi town, where we’d sell it to the local sundry store in exchange for just a few ringgit.”

Such oral histories offer rich ethnographic glimpses into the early coffee trade in Sarawak. In fact, even during the 20th century, most local roasters in Sarawak—just like their counterparts in Peninsular Malaysia—relied on Robusta imports from Indonesia or Vietnam for their traditional blends. Liberica was, at best, a minor supporting ingredient.

Earthlings Coffee team cupping with indigenous communities across Sarawak’s interior—shown here: members of the Kelabit community on the Bario Plateau (Bario Highlands).

Coffee training night in a longhouse, 2024

Today, it is clear that this legacy market structure and pricing cannot sustain a viable specialty coffee industry. However, recent field research and industry reports show a growing interest among urban coffee communities in Sarawak to re-evaluate Liberica. Many are now experimenting with scientific post-harvest processes—from selective picking to controlled fermentation and drying—in an attempt to elevate Liberica from a “village drink” into a specialty product.

Reviving Quality and Genetic Curiosity

Notably, Black Bean Coffee has long been a quiet pioneer in this space. In 2019, the Sarawak Department of Agriculture and Earthlings Coffee signed an MoU at the Borneo Coffee Symposium, signaling a formal commitment to pushing Liberica into the specialty realm.

Genetic diversity of Liberica in Sarawak

Beyond improved processing, another fascinating development has been the discovery of multiple unique Liberica variants across Sarawak’s interior. Based on our recent research and sample collection, Liberica cultivated in Sarawak exhibits striking morphological, sensory, and phenotypic differences from those grown in Peninsular Malaysia.

I have personally shared these Sarawak-grown Liberica samples with several West Malaysian coffee professionals, and all agreed that the flavor profile is noticeably different. In fact, the only comparable variants I have encountered were at a coffee research center in South India, and even those displayed distinct differences from Sarawak’s types.

These current Liberica variants are now undergoing full-lineage genomic research to uncover their origins and potential agronomic or sensory traits.

A Legacy of Agricultural R&D in Sarawak

Sarawak’s agricultural research and development tradition—spanning research, extension, and demonstration—can be traced back to the post-WWII era. Research stations such as Semongok and Tarat were established to carry out scientific studies, farmer training, and field extension. According to official records, the Agricultural Research Centre (ARC) began laying the foundation for varietal development, infrastructure, and agronomic outreach between the 1970s and 1990s, forming today’s diverse crop research network.

In recent years, the ARC has played a key role in the coffee sector, particularly in seedling supply, technical consultations, quality education, and community engagement. Key individuals within the institution, such as Diana Jitam and Wendy Luta, have also been actively involved in promoting the development of the coffee industry in Sarawak through various means.

Government Policy and Post-Pandemic Coffee Momentum

Coffee has been designated a priority crop by the Sarawak state government. In select districts, farmers are offered start-up capital and incentive programs. The government also supported the 2019 Borneo Coffee Symposium, singling top-down momentum to encourage long-cycle crop investment. Following this, Liberica cultivation began spreading across Sarawak.

Today, many of the seedlings distributed around the time of the pandemic have matured and are beginning to yield.

Academic Engagement and Functional Research

On the academic front, research on Liberica by-products—such as silver skin, coffee blossoms, and cascara—has begun to appear in peer-reviewed journals, reflecting growing interest in the entire coffee value chain.

Currently, it is estimated that more than 4,000 acres of Liberica are under cultivation by both indigenous smallholders and large estates across Sarawak, with over 2,000 acres expected to reach fruit-bearing maturity within two years.

The Sarawak Liberica Refinement Project (SLRP)

Since 2017, Earthlings Coffee Workshop, in collaboration with ARC, has been piloting the Sarawak Liberica Refinement Project (SLRP) across rural communities. The project is grounded in five core principles:

Quality improvement

Sustainability

Farmer empowerment

Transparency

Market access

Rather than binding farmers with rigid contracts, SLRP promotes open engagement, refining post-harvest methods and grading systems to elevate Liberica into the specialty coffee segment.

What Has Been Done So Far

Research Officer from ARC, Diana Jitam.

Various initiatives have been carried out on-site at research stations like Tarat, as well as in villages across the state. These include:

Breeding programs

Root system dissections of old trees

Diverse fermentation experiments

Specialised drying curves

Moreover, the SLRP and ARC teams have hosted cupping exchanges, dryer infrastructure upgrades, and knowledge workshops in regions such as Sibu, Sarikei, Tringgus, Munggu Kupi, Bario, and Lawas. A transparent price–quality matrix is also being developed to reduce information asymmetry and protect farmers from market exploitation.

The Bigger Picture: Raising the Baseline

Coffee refinement training conducted by the Earthlings and ARC teams across rural Sarawak.

Some individual producers, inspired by global coffee auctions, are starting to experiment with ultra-premium “microlots”. While this ambition is commendable, the SLRP maintains that for the broader smallholder community in Sarawak, the priority should be to first ensure baseline consistency:

“Focus first on defect control, moisture stabilisation, sanitary fermentation, and proper drying curves. Only then experiment with flavour-forward processing.”

The future of Sarawak Liberica, it argues, lies not in chasing one or two legendary lots, but in producing thousands of kilos of clean, repeatable, and well-communicated coffees that the broader specialty market can confidently adopt.

Once this foundation is in place, Sarawak—and Malaysia as a whole—has a chance to re-enter the global coffee map under the name of Liberica

Notes:This article is translated from the original Chinese piece published in the feature section of Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商報), dated September 12, 2025.